more thoughts on the upcoming event, Monday night

The Beach House will host the world-class (and world-famous) artist Don Bachardy on Monday night, and in advance of that, I just wanted to explore a few ideas hinted at in the previous blog post.

Don Bachardy has been part of my life well before I ever met him. A poetry mentor, Robert Peters, lives with his amazing life partner Paul Trachtenberg, and it was in their house --- filled with books and art and magic and laughter and thought and home-made plum cobbler --- that I first saw a Bachardy original. It was a portrait of Peters that had force and truth unlike anything I had seen before:

I grew up in a working class neighborhood and the people around me didn't collect art or own nice books. Now, older and more experienced, I am used to that option more, and the idea of owning a signed original or a limited edition is part of my day-to-day reality. But the first work by a living artist that I saw away from a museum was Bachardy's painting of Bob Peters. He's a smart and formidable thinker, Robert Peters is, and the author of "no holds barred" criticism. He looks out here ready to tell the world exactly what he sees.

One might notice that it is not a pretty picture. Bachardy is always honest but never intentionally flattering. If you want somebody to lie to you, he ain't your boy.

Portraits though are complicated things. One of the things I want to cover in our dialogue will be the dual issues of presentation (how a work is framed, lit, hung, and seen by "us," the public) and interpretation (how a work is explained or understood or conceptualized). If we take this Ingres from the Norton Simon, for example....

.... it's usual to talk about the identity of the sitter, and of course the wonderful technical skill in how the paint is handled, the light, the expression of masculine ideals, and so on. Yet we also have less obvious things, such as the frame itself, the way that the fame (or lack of fame) of the artist "hides" the work, or even our own fatigue as we stand there, inside the museum itself, hungry or late for an appointment or wondering when the parking meter will expire.

The artists, too, have to get through a certain amount of static. Last blog I mentioned fame as an issue for the artist to deal with as well and I hope we can have some fun exploring this. What about the very basic materials, such as the paint sets themselves?

What does an artist's choice of color mean, and how should she or he handle the liquidity or opacity of the medium itself? In this portrait of me by Bachardy, I came to the sitting in a medium blue t-shirt. Look how fabulous that shirt becomes, though, once he decides to paint my portrait on top of a previously painted abstraction.

A sitting is a contest of wills, a partnership, a dance, a seduction. We'll talk about this on Monday night, and about the role of the sitter in the collaboration that makes a good piece be great, or, conversely, dooms the effort to failure. Just as a side note, I will say that being looked at intently (and holding a still pose) is much harder work than people suppose.

Bachardy does not work from sketches or make preliminary studies: he looks and paints, directly, more like a bull fighter than somebody, say, rehearsing a play. I have seen him do it a dozen times with all manner of sitters, and how he does it remains beyond description. He starts with the eyes usually, but his "pencil" is the brush itself: he looks, dips the brush in color, and makes magic happen.

This lad portrayed here is one of the "orphans" about whom I plan to write. He is shown here reclining on pillows (not drawn, just implied by negative space) which adds to his slightly strange, dislocated, lost-in-space attitude. It may be hard to see in this blog version, but he his pierced nipples. Another topic we'll try to deal with Monday honestly and yet delicately will be the issue of sexuality and art. After all, this close-up from the Norton Simon will seem like "normal" high-class art, not pornography, or at least will be that for most people.

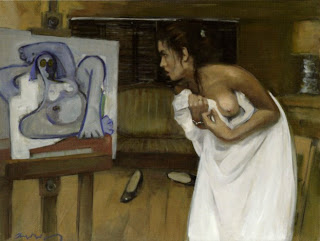

A gal's luscious bottom is accepted as okay, especially if we thrown in a classical allusion or some white drapery. Yet what if this were a loving and detailed perusal of a man's backside, ripe as summer pears? We accept a passive heterosexuality as normal and allowable, but gay art or even just a neutral male nude and oh my goodness, things get tense quickly. Bosoms and booties, yes; nipples and nipple rings, no.

Size matters, and often we see art (as here on this blog) in less than ideal formats. Bachardy and I both happened to see David Hockney's last big show in London, the blockbuster event at the Royal Academy of Art, and that included some monumentally-sized pieces.

We should talk about what it's like to make and see large art, and if art history books can even portray those pieces convincingly enough or not.

This is one heck of a big baby, fresh from the womb and still bloody with the trauma of birth. (This shot is from Christchurch, New Zealand, but that art museum is now closed, after a series of major earthquakes.) Size, materials, presentation: all of these add (or subtract) from the art experience.

Great portraits capture the spirit of the times, besides helping us to understand the sitter himself. This self-portrait by Nussabaum from 1943 shows him with his Jewish identity card hiding in a ghetto corner, a ruined landscape towering above him. The painter is clearly a wounded, trapped animal in a brutal, prison-like world. The painter had reason to be fearful: within a year, the Nazi genocide took his life.

We are used to thinking of art museums as places to study paintings, but in our day to day lives, most people think of their iPhones as an essential tool for memory, not a sketch pad or even a drawing function on an iPad. Don and I on Monday are going to talk about the way that photography influences people's perceptions of what a "portrait" should look like, and the reasons a painter might resist or by-pass photography.

In passing, I should mention that Don Bachardy lives in Santa Monica and his main gallery also is in Santa Monica too. Craig Krull Gallery in the Bergamot Station complex (2525 Michigan Ave) shows Don Bachardy's work in small but well-curated exhibits, and it's my understanding that there will be another one in early or mid-2013. It's something to look forward to. That's an art space that also is generous with photography, and Craig Krull Gallery exhibits another artist I admire greatly, the photographer Michael Light (shown here with a very very large book, at an event a few months ago).

At the end of sittings, Bachardy asks his collaborators (victims? ... it depends on one's perspective --- as implied above, some people expect to be flattered in a falsely beautiful version) to sign and date the works. Maybe in a few hundred years a handwriting expert will find a Ph.D. thesis in the analysis of how different people present their names. Some even practice on a scratch pad first. Here the novelist Danny Vilmure signs his recently completed portrait.

If all of these theoretical issues seem a bit technical or like a lesson in "how many angels can dance on the head of a pin," I want to promise our Annenberg Beach House community that even if I were prone to going off the theoretical deep end, Don won't put up with it. He's funny and very very very much alive, with a sly wit and an immense awareness of the world around us. Nobody ever uses the words "pretentious" or "stuck up" about him. He will keep me honest and on track.

There will be a question and answer period on Monday, and I do hope to see you there. We start at 6:30 pm, in the Annenberg Community Beach House and Cultural Center, 415 Pacific Coast Highway, just north of Santa Monica Pier.

A map can be seen on this link:

http://beachhouse.smgov.net/visit-us/getting-here-and-parking.aspx

Don Bachardy and I look forward to meeting you.

The Beach House will host the world-class (and world-famous) artist Don Bachardy on Monday night, and in advance of that, I just wanted to explore a few ideas hinted at in the previous blog post.

Don Bachardy has been part of my life well before I ever met him. A poetry mentor, Robert Peters, lives with his amazing life partner Paul Trachtenberg, and it was in their house --- filled with books and art and magic and laughter and thought and home-made plum cobbler --- that I first saw a Bachardy original. It was a portrait of Peters that had force and truth unlike anything I had seen before:

I grew up in a working class neighborhood and the people around me didn't collect art or own nice books. Now, older and more experienced, I am used to that option more, and the idea of owning a signed original or a limited edition is part of my day-to-day reality. But the first work by a living artist that I saw away from a museum was Bachardy's painting of Bob Peters. He's a smart and formidable thinker, Robert Peters is, and the author of "no holds barred" criticism. He looks out here ready to tell the world exactly what he sees.

One might notice that it is not a pretty picture. Bachardy is always honest but never intentionally flattering. If you want somebody to lie to you, he ain't your boy.

Portraits though are complicated things. One of the things I want to cover in our dialogue will be the dual issues of presentation (how a work is framed, lit, hung, and seen by "us," the public) and interpretation (how a work is explained or understood or conceptualized). If we take this Ingres from the Norton Simon, for example....

.... it's usual to talk about the identity of the sitter, and of course the wonderful technical skill in how the paint is handled, the light, the expression of masculine ideals, and so on. Yet we also have less obvious things, such as the frame itself, the way that the fame (or lack of fame) of the artist "hides" the work, or even our own fatigue as we stand there, inside the museum itself, hungry or late for an appointment or wondering when the parking meter will expire.

The artists, too, have to get through a certain amount of static. Last blog I mentioned fame as an issue for the artist to deal with as well and I hope we can have some fun exploring this. What about the very basic materials, such as the paint sets themselves?

What does an artist's choice of color mean, and how should she or he handle the liquidity or opacity of the medium itself? In this portrait of me by Bachardy, I came to the sitting in a medium blue t-shirt. Look how fabulous that shirt becomes, though, once he decides to paint my portrait on top of a previously painted abstraction.

A sitting is a contest of wills, a partnership, a dance, a seduction. We'll talk about this on Monday night, and about the role of the sitter in the collaboration that makes a good piece be great, or, conversely, dooms the effort to failure. Just as a side note, I will say that being looked at intently (and holding a still pose) is much harder work than people suppose.

Bachardy does not work from sketches or make preliminary studies: he looks and paints, directly, more like a bull fighter than somebody, say, rehearsing a play. I have seen him do it a dozen times with all manner of sitters, and how he does it remains beyond description. He starts with the eyes usually, but his "pencil" is the brush itself: he looks, dips the brush in color, and makes magic happen.

This lad portrayed here is one of the "orphans" about whom I plan to write. He is shown here reclining on pillows (not drawn, just implied by negative space) which adds to his slightly strange, dislocated, lost-in-space attitude. It may be hard to see in this blog version, but he his pierced nipples. Another topic we'll try to deal with Monday honestly and yet delicately will be the issue of sexuality and art. After all, this close-up from the Norton Simon will seem like "normal" high-class art, not pornography, or at least will be that for most people.

A gal's luscious bottom is accepted as okay, especially if we thrown in a classical allusion or some white drapery. Yet what if this were a loving and detailed perusal of a man's backside, ripe as summer pears? We accept a passive heterosexuality as normal and allowable, but gay art or even just a neutral male nude and oh my goodness, things get tense quickly. Bosoms and booties, yes; nipples and nipple rings, no.

Size matters, and often we see art (as here on this blog) in less than ideal formats. Bachardy and I both happened to see David Hockney's last big show in London, the blockbuster event at the Royal Academy of Art, and that included some monumentally-sized pieces.

We should talk about what it's like to make and see large art, and if art history books can even portray those pieces convincingly enough or not.

This is one heck of a big baby, fresh from the womb and still bloody with the trauma of birth. (This shot is from Christchurch, New Zealand, but that art museum is now closed, after a series of major earthquakes.) Size, materials, presentation: all of these add (or subtract) from the art experience.

Great portraits capture the spirit of the times, besides helping us to understand the sitter himself. This self-portrait by Nussabaum from 1943 shows him with his Jewish identity card hiding in a ghetto corner, a ruined landscape towering above him. The painter is clearly a wounded, trapped animal in a brutal, prison-like world. The painter had reason to be fearful: within a year, the Nazi genocide took his life.

We are used to thinking of art museums as places to study paintings, but in our day to day lives, most people think of their iPhones as an essential tool for memory, not a sketch pad or even a drawing function on an iPad. Don and I on Monday are going to talk about the way that photography influences people's perceptions of what a "portrait" should look like, and the reasons a painter might resist or by-pass photography.

In passing, I should mention that Don Bachardy lives in Santa Monica and his main gallery also is in Santa Monica too. Craig Krull Gallery in the Bergamot Station complex (2525 Michigan Ave) shows Don Bachardy's work in small but well-curated exhibits, and it's my understanding that there will be another one in early or mid-2013. It's something to look forward to. That's an art space that also is generous with photography, and Craig Krull Gallery exhibits another artist I admire greatly, the photographer Michael Light (shown here with a very very large book, at an event a few months ago).

At the end of sittings, Bachardy asks his collaborators (victims? ... it depends on one's perspective --- as implied above, some people expect to be flattered in a falsely beautiful version) to sign and date the works. Maybe in a few hundred years a handwriting expert will find a Ph.D. thesis in the analysis of how different people present their names. Some even practice on a scratch pad first. Here the novelist Danny Vilmure signs his recently completed portrait.

If all of these theoretical issues seem a bit technical or like a lesson in "how many angels can dance on the head of a pin," I want to promise our Annenberg Beach House community that even if I were prone to going off the theoretical deep end, Don won't put up with it. He's funny and very very very much alive, with a sly wit and an immense awareness of the world around us. Nobody ever uses the words "pretentious" or "stuck up" about him. He will keep me honest and on track.

There will be a question and answer period on Monday, and I do hope to see you there. We start at 6:30 pm, in the Annenberg Community Beach House and Cultural Center, 415 Pacific Coast Highway, just north of Santa Monica Pier.

A map can be seen on this link:

http://beachhouse.smgov.net/visit-us/getting-here-and-parking.aspx

Don Bachardy and I look forward to meeting you.